Mankind is fast approaching the ultimate adventure: the colonization of outer space. In a few decades we will take control of the Moon and the planet Mars. The adventure will continue and, once we have the necessary technologies, we will travel to the stars.

Although we will have to wait a long time for this stage of humanity’s adventure to begin, there are scientists wondering what will happen to the language spoken by those who will embark on long interstellar travel and that / or will be establishing colonies on the surface of extrasolar distant planets.

In April 2020, an article entitled “Language Development During Interstellar Travel” was published in Acta Futura, an ESA journal dedicated to advanced concepts. The study is signed by two researchers, A. Mckenzie, of the Department of Linguistics at the University of Kansas, and J. Punske, an associate professor at the University of Southern Illinois.

Although I have very poor knowledge of linguistics, the text of the two fascinated me from the beginning, so I read it with great enthusiasm. It begins: “This study explores the consequences of language changes during interstellar travel and interplanetary colonization. The language changes as the communities become more isolated from each other, so that the long isolation of a traveling community can lead to a language incomprehensible by the community from which it left. The problem will escalate later, when new communities arrive, which will, in turn, have a modified language compared to that of the first travelers.”

On the University of Kansas website, McKenzie said: “If you are in the tenth generation on an interstellar spacecraft, you will find that new concepts and new social issues have emerged and people have created new ways to talk about them. This is how a new spaceship-specific vocabulary appears. Those left on Earth may never invent the same words as long as they do not need them. And as you move away, communication with your family will become increasingly rare. […] Eventually it will reach the point where there will be no more real contact with the Earth, less the technical data transmitted periodically. Given that the language will change on the spacecraft during the voyage and during colonization, the following question naturally arises: Will we have to make the effort to learn the language from the moment we leave Earth? The answer is yes. We will have to learn it in order to be able to read the flight manuals, to send messages home, etc. But it must also be borne in mind that there, on Earth, the language will also evolve. So the ones left at home, will have to use, when they communicate with them, the language from the moment the crew of space colonizers set off. It’s as if we’re currently using Latin in order to communicate.”

Looking to the past

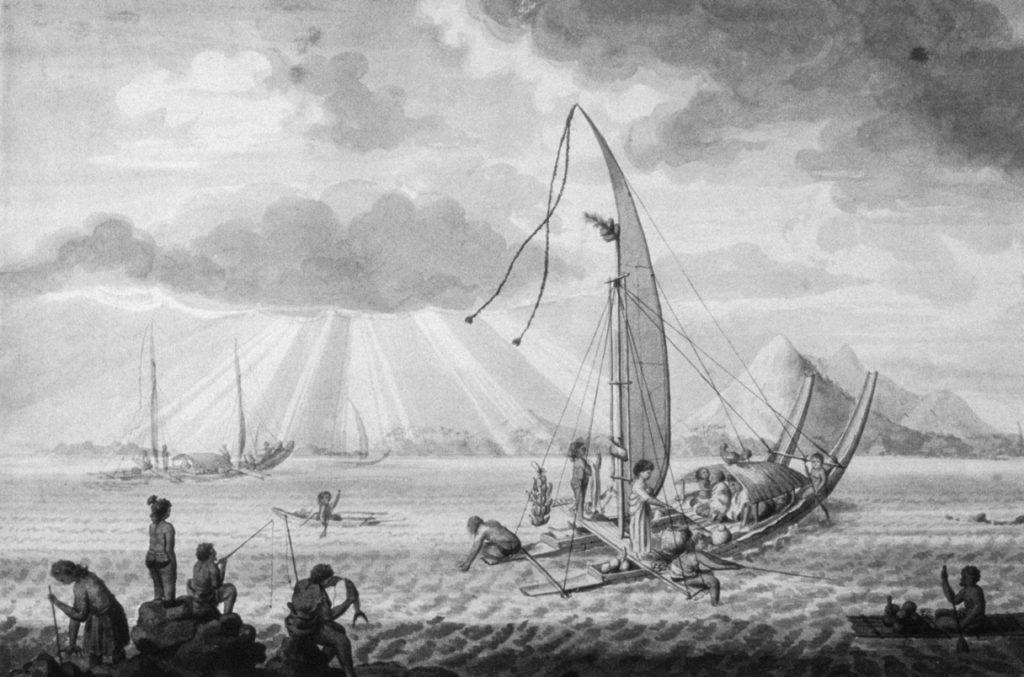

In the history of humanity we have several situations in which communities, whether larger or smaller, have isolated themselves from their homeland. Probably the history of the Polynesians gives us the best clues about the divergent evolution of the language in communities that no longer communicate, or that hardly communicate, with those left at home.

About two and a half millennia ago, they began colonizing the Pacific islands. Around the 500’s, groups of Polynesians reached the Hawaiian Archipelago and Easter Island. By the 1,000s they were arriving in New Zealand.

To date, almost 30 Polynesian languages have been cataloged. None of them are spoken by populations of more than half a million people and half of them are spoken by populations of less than a thousand members. All Polynesian languages seem to come from a common language, called Proto-Polynesian, which spread to the area between Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Wallis and Futuna.

Since its Polynesians colonized uninhabited islands and, most often, lived in complete isolation, the study of the languages spoken by them is a “genuine linguistic laboratory”, the authors of the study note, without going into further detail.

By the way, I would invite you to imagine this adventure of the old Polynesians, who set out on long journeys, most often without knowing if at the end of the road a welcoming land awaits them. They knew they would face enormous dangers, they knew it would be almost impossible for them to return home. And yet they managed to colonize many of the Pacific islands in a span of two millennia. Somehow there is a gene that urges us to go beyond the boundaries of the known, a gene that has remained active to this day.

We now have a huge advantage over the Polynesians. We know where we want to go and we will not set off until we know the destination in detail, no matter how far away it is, and without preparing the technological resources to ensure the survival of the settlers. We are not pressed for time yet, we can still hope that our planet will provide us with the resources necessary for the survival of civilization, if we learn to take care of it.

Returning to the two American researchers, they show, in the quoted article, that we do not have historical information about the chronology of the divergent evolution of the Polynesian language. Here is a small remark. In 1985, the great Romanian mathematician Solomon Marcus published a book that I read from cover to cover. It was simply entitled “Time.”

Among other things, it addressed the issue of “linguistic time”. I don’t have the book anymore but, fortunately, at Paralela 45 publishing house, in 2011, the text was resumed in the anthology “Universal Paradigms”. I quote from Solomon Marcus: “Linguists, anthropologists, and archaeologists have long been concerned with the temporal perspective of language development. While all authors agreed that the degree of differentiation within a family of languages increases with the historical time of development of these languages, few suspected that more accurate information could be obtained on this dependence. Indeed, such heterogeneous influences on language development did not give much hope for more rigorous results in this area, especially when it comes to those periods in the history of a language for which there is no direct information. Under these conditions, it is easy to understand the novelty of the hypothesis raised in 1952 by Morris Swadesh, after which the basic vocabulary, in contrast to the mass of the vocabulary, changes very slowly, at a constant rate, the same for all the languages of the earth.”

Solomon Marcus then presents Swadesh’s hypothesis, which in turn is divided into four hypotheses:

“1. A certain relatively small part of the vocabulary of any language (part called the basic vocabulary) is much less subject to change than the rest of the vocabulary.

- The rate of change (in technical terms: retention rate) of basic vocabulary is relatively constant over time. More precisely, if after an evolution of a thousand years the basic vocabulary remained unchanged in the proportion of p% (where p is usually higher than 70), then, after another thousand years, an approximately the same proportion of p% of the remaining vocabulary remains intact; and after a third millennium, about the same proportion of p% of the vocabulary that has endured two millennia will remain intact and so on.

- The proportion of p% (called the retention rate) we referred to earlier is about the same for all the languages of the earth. In other words, the retention rate of the basic vocabulary is approximately the same in all languages.

- As a consequence of the previous hypothesis, if the proportion of those words in the basic vocabulary that are genetically similar and have a similar meaning is known for any two languages, then (if disturbing factors such as migrations, conquests or other social contacts did not occur which could slow down or speed up the normal process of differentiation) the time elapsed since the two languages began to differentiate from their mother tongue can be assessed.”

Modern explorers

The Polynesian Language Laboratory is a useful tool for seeing how languages spoken by future space explorers will evolve. However, as the two American researchers point out, “we need to take into account the cultural changes that have taken place in the meantime.” The two identify three cultural changes that will influence the evolution of language.

First, they talk about language policy: “In everyday life, people can use whatever language suits them. When it comes to international or professional cooperation, constraints begin to arise. The existence of a common language, or a small set of languages, is important for cooperation and becomes crucial for the success of a mission.” From this perspective, it is necessary for “any colony, or long-haul flight, to consider the establishment of a well-defined language policy.” Such a policy will influence the pace of language change.

Secondly, education must be taken into account. “Unlike in the past, in modern times almost all children go to school. Children are an important component in changing the language.” School is an important factor in preserving the language, by imposing strict grammar and style rules. This does not mean that we are not witnessing a continuous evolution of it. Even today, dictionaries are enriched with new words. “The same thing will happen with interstellar travel or colonies on extrasolar planets. Even though the schools on board will rigorously teach, say, terrestrial English, children will gradually develop a spacecraft dialect that, over time, will move further and further away from the English spoken on Earth [at the start of mission]. […] After a few generations, crew members will no longer have to learn ground English, excepting the need of reading flight and maintenance manuals and other historical documents. In the case of a multilingual crew, this process will be similar for each language involved.”

Thirdly, the evolution of telecommunications must be taken into account. For a long time, communities lived somewhat isolated from each other. With the information revolution, things have changed dramatically. “Contact slows or prevents language divergence, and the national media promotes a single identity with a neutral dialect, so we could conclude that these dialects will mix over time. This conclusion is contradicted by what can be seen today. We find that the image is much more complex. While some dialects are moving towards a standard dialect, promoted by education and the media, other dialects will move away from it, as a marker of socio-economic identity, a way to preserve their own identity in a homogenized culture.”

Something similar will happen in the case of very long space travel. The divergent evolution of the language will occur, despite the preservation of radio communications with those left at home. Evolution will become much faster when, due to the distance, radio messages between Earth and the spacecraft will be received years after their transmission. Let’s not forget that even at home, on Earth, we will witness a continuous evolution of language. In these conditions, for the communications between the space explorers and those left on Earth, an “archaic” language will be used, the one spoken at the time of departure. “It’s something analogous to the use of Latin by the Catholic Church.”

The two American authors also specify an important aspect: “If we send multiple crews to the colonies, new problems will arise. History shows that, in the case of trips of several months, the time will not be enough for the appearance of new languages, so, once the colony has established its own dialect, the new arrivals will be able to assimilate it quickly. […] However, in the case of voyages that will take place over several generations, a completely different dialect from that of the first settlers will develop on board each spacecraft. […] Each new crew arriving in the colony will essentially represent a new group of linguistic emigrants. Will these groups be discriminated against until their children and grandchildren learn the local language? Could a communication channel be established, before arrival, for newcomers to learn the local language before landing in the colony?”

Conclusion

It will certainly take several generations for large groups of people to move on to other stars. There will be many technical problems to be solved and, at present, we can barely guess the solutions to them. I’ve written about it on other occasions. I have now dared to approach a subject related to linguistics in order to better outline the problems of the future.

I wanted to show you that not only researchers in the field of exact sciences are concerned with long space travel, but also those in the field of humanities. For me, that’s a good sign. Scientists are concerned not only about the immediate or medium future but also about the distant future. This makes me repeat: we will definitely colonize distant extrasolar planets!