The mystery of the lost city of Troy is one of the most captivating tales in archaeology and mythology. Troy, an ancient city immortalized by Homer’s epic poems “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey,” was long considered a legend by many scholars.

The city was thought to be purely mythical until its eventual discovery in the 19th century. This article delves into the fascinating journey of how the mystery of Troy was solved, shedding light on the historical and archaeological efforts that brought this ancient city to life.

The Legend of Troy

The legend of Troy primarily comes from Homer’s epic poems, which narrate the story of the Trojan War. According to “The Iliad,” the war was sparked by the abduction of Helen, the wife of the Spartan king Menelaus, by Paris, the prince of Troy.

The Greek forces, led by King Agamemnon, besieged the city for ten years. The story culminates in the Greeks’ cunning use of the Trojan Horse, a wooden structure hiding soldiers inside, which allowed them to enter and destroy Troy.

For centuries, many scholars and historians believed the story of Troy was purely mythological, a creation of poetic imagination rather than historical fact. The actual existence of Troy, its location, and the historical accuracy of the Trojan War remained subjects of speculation and debate.

Early Searches and Theories

The quest to uncover the real Troy began in earnest in the early 19th century. Several scholars and adventurers set out to find the city mentioned by Homer. Among the early explorers was Charles Maclaren, a Scottish journalist and geographer, who in 1822 proposed that the ancient city of Troy might be located in Hisarlik, a mound in northwestern Turkey.

Hisarlik, situated near the Dardanelles strait, was one of the many proposed locations, but there was no concrete evidence to support this theory at the time.

Heinrich Schliemann: The Man Who Found Troy

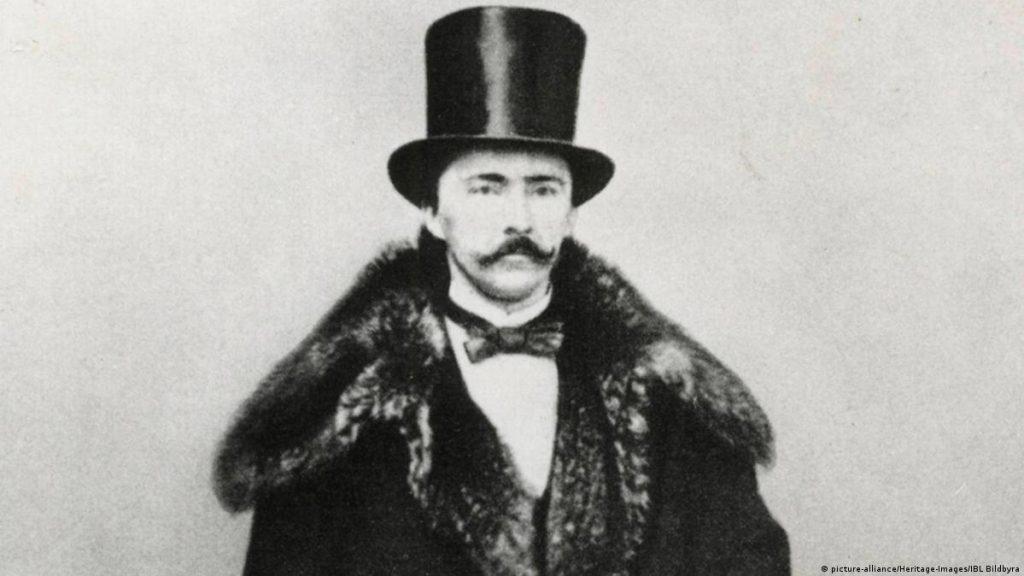

The true breakthrough in the search for Troy came with Heinrich Schliemann, a wealthy German businessman and self-taught archaeologist with a passion for Homeric literature. Schliemann was convinced that Homer’s Troy was a real place and set out to find it.

In 1870, Schliemann began excavations at Hisarlik, inspired by the earlier suggestion of Charles Maclaren and the work of Frank Calvert, an amateur archaeologist who had also identified Hisarlik as a potential site.

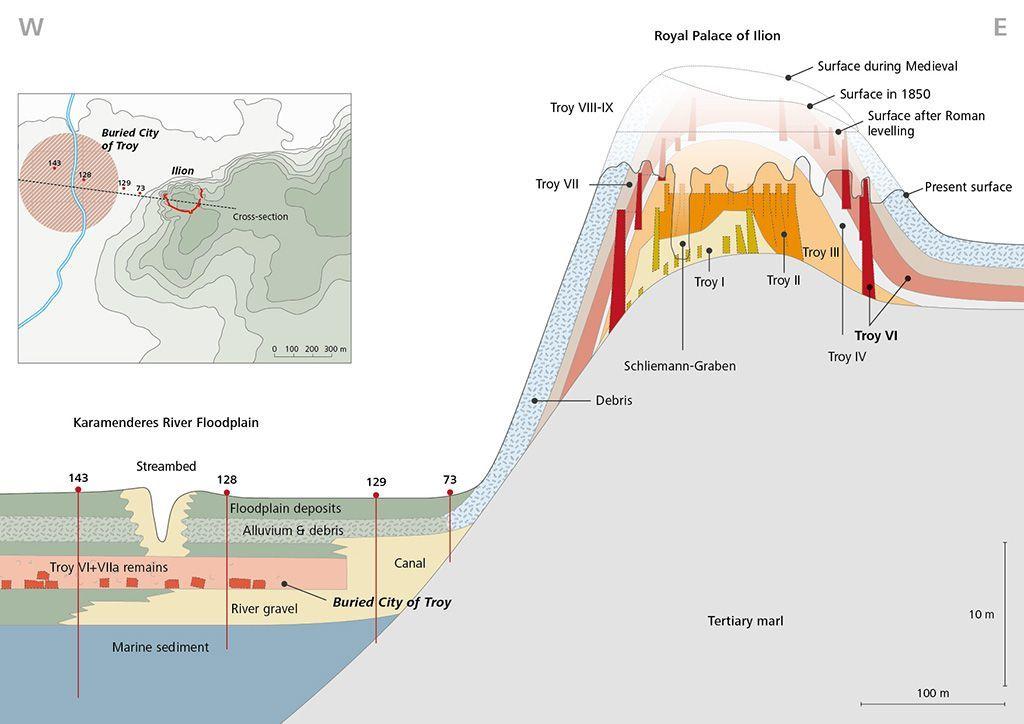

Schliemann’s excavations were groundbreaking, both literally and figuratively. He uncovered several layers of ancient cities built on top of each other, suggesting that Hisarlik had been inhabited for thousands of years. Among these layers, Schliemann identified what he believed to be the remains of Homer’s Troy. His most significant discovery came in 1873 when he unearthed a large cache of gold and other artifacts, which he dubbed “Priam’s Treasure” after the legendary king of Troy.

Controversies and Further Excavations

Schliemann’s methods, however, were often criticized. His excavation techniques were considered crude and destructive, as he used dynamite to blast through the layers of the site, potentially destroying valuable archaeological evidence. Moreover, his identification of “Priam’s Treasure” and the layer he associated with Homeric Troy (which he called Troy II) was later contested by other archaeologists.

Subsequent excavations by Wilhelm Dörpfeld, who worked with Schliemann, and later by Carl Blegen, an American archaeologist, provided more refined and systematic studies of Hisarlik. Blegen’s work in the 1930s identified another layer, Troy VIIa, which he proposed as the likely candidate for the Troy of Homer’s epics. Troy VIIa showed signs of violent destruction and was dated to the 13th century BCE, aligning with the traditional timeframe of the Trojan War.

Modern Archaeological Insights

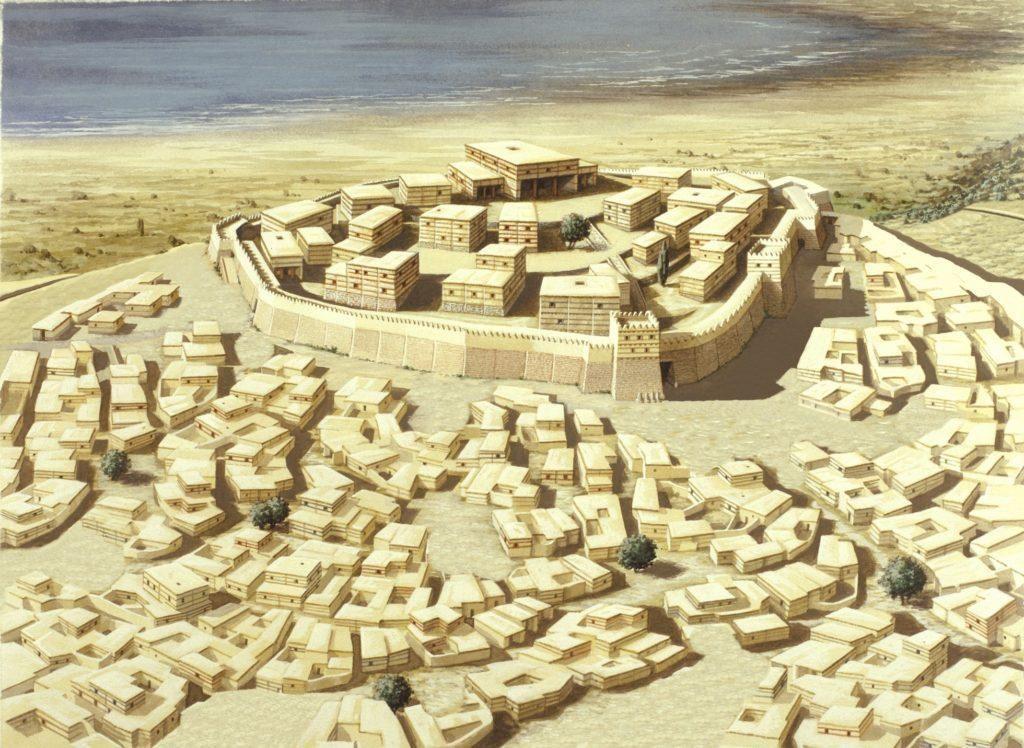

The most comprehensive excavations at Hisarlik have been conducted by a team led by Manfred Korfmann, a German archaeologist, starting in the late 20th century. Korfmann’s work utilized modern archaeological techniques and technology, providing a more detailed understanding of the site. His team discovered evidence of a significant city with impressive fortifications, extensive lower town areas, and complex infrastructure, indicating that Troy was a major center of commerce and culture in the ancient world.

One of the most significant findings was the confirmation that Troy had a large lower town, previously overlooked in earlier excavations. This discovery suggested that Troy was much larger and more complex than previously thought, capable of supporting a substantial population.

Additionally, archaeological evidence from surrounding areas indicated that Troy was indeed involved in conflicts during the late Bronze Age, lending credence to the historical basis of the Trojan War.

The Historical Basis of the Trojan War

While the exact details of the Trojan War as described by Homer remain a blend of myth and history, archaeological evidence supports the existence of a city that experienced significant destruction around the time traditionally associated with the war.

The discovery of weapons, fortifications, and evidence of a conflagration in Troy VIIa aligns with the narrative of a prolonged and destructive conflict.

Furthermore, Hittite texts from the same period mention a city called Wilusa, which is believed to be the Hittite name for Troy, and references to a kingdom called Ahhiyawa, thought to be the Hittite name for the Greeks (Achaeans). These texts provide external corroboration of a city corresponding to Troy and suggest interactions, possibly hostile, between the Hittites and the Mycenaean Greeks.

The mystery of the lost city of Troy has been largely solved through the dedicated efforts of archaeologists over the past century and a half. From Heinrich Schliemann’s initial, controversial discoveries to the modern, methodical excavations of Manfred Korfmann, the city of Troy has been brought out of the realm of legend and into the annals of history.

Today, the site of Hisarlik is recognized as the location of ancient Troy, a city that truly existed and played a significant role in the Bronze Age world.

While the romanticized version of the Trojan War as told by Homer may never be fully confirmed, the archaeological evidence provides a compelling case that there was indeed a city of Troy that experienced a catastrophic event, likely remembered in the oral traditions that eventually became “The Iliad.”

The tale of Troy remains a poignant reminder of how myth and history often intertwine, and how the perseverance of those who seek the truth can uncover the real stories behind the legends.

Unveiling Troy: The Journey of Discovery

The discovery of Troy is not just a tale of archaeological triumph but also a story filled with intrigue, passion, and controversy. Heinrich Schliemann, the man credited with discovering Troy, had an adventurous life that reads like an epic itself.

Heinrich Schliemann: A Man on a Mission

Heinrich Schliemann was born in 1822 in Neubukow, Germany. He grew up in a modest family and was fascinated by Homer’s epics from a young age. Schliemann’s early career was not in archaeology but in business. He became a successful merchant and amassed considerable wealth, which later enabled him to pursue his passion for ancient history.

Schliemann’s belief in the historical accuracy of Homer’s works was unusual for his time. Most scholars regarded “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” as purely literary creations. However, Schliemann was determined to prove them wrong. His self-confidence and financial independence allowed him to embark on an ambitious quest to locate the fabled city of Troy.

Excavations Begin at Hisarlik

In 1868, Schliemann visited the site of Hisarlik in northwestern Turkey, which had been suggested by Frank Calvert, an amateur archaeologist. Calvert had already conducted preliminary digs and believed that Hisarlik was the site of ancient Troy. Schliemann partnered with Calvert and began extensive excavations in 1870.

Schliemann’s approach to archaeology was unorthodox and often destructive. He used large-scale digging methods and dynamite, which caused significant damage to the site. His haste and eagerness to find Homeric Troy led him to focus on deeper layers, sometimes ignoring or destroying evidence from later periods.

Despite these methods, Schliemann made remarkable discoveries. He unearthed multiple layers of settlements, revealing that Hisarlik had been inhabited continuously from the early Bronze Age to the Byzantine period. Among these layers, he identified what he believed to be the remains of Priam’s Troy, particularly in a layer he called Troy II.

Priam’s Treasure and Its Controversy

In 1873, Schliemann made one of his most famous discoveries: a cache of gold and artifacts, which he dubbed “Priam’s Treasure.” He believed these treasures belonged to King Priam, the ruler of Troy during the Trojan War. Schliemann smuggled the treasure out of Turkey, which led to legal disputes with the Ottoman government.

The authenticity of “Priam’s Treasure” and Schliemann’s identification of Troy II as the Homeric Troy were later questioned. Scholars argued that Troy II was too early to be the city described by Homer and that the treasure might belong to a different period.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld and Carl Blegen: Refining the Search

After Schliemann’s death in 1890, Wilhelm Dörpfeld, one of his collaborators, continued the excavations. Dörpfeld introduced more systematic methods and identified several distinct layers of occupation at Hisarlik. He proposed that Troy VI, with its impressive walls and architecture, might be the Homeric Troy. However, Troy VI showed no signs of destruction by war, which posed a problem for this theory.

In the 1930s, Carl Blegen, an American archaeologist, resumed excavations at Hisarlik. Blegen’s meticulous work led him to identify Troy VIIa as a more likely candidate for Homer’s Troy. This layer showed evidence of violent destruction, including collapsed walls, burned debris, and human remains, suggesting a catastrophic event. Blegen dated Troy VIIa to the 13th century BCE, aligning with the traditional timeframe of the Trojan War.

Modern Archaeology at Troy

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, further excavations at Hisarlik were conducted by Manfred Korfmann and his team from the University of Tübingen. Korfmann’s work provided a more comprehensive picture of Troy’s history and its regional significance.

Korfmann used advanced archaeological techniques, including geophysical surveys, to explore the lower city, previously neglected in earlier excavations. These surveys revealed a much larger settlement than previously thought, with extensive fortifications and complex urban infrastructure.

The Lower City and Its Significance

The discovery of the lower city changed the understanding of Troy’s size and importance. The lower city, surrounded by defensive ditches and walls, extended over a large area and included residential quarters, workshops, and public buildings. This indicated that Troy was a major urban center with significant economic and strategic value.

Artifacts and ecofacts from the site showed evidence of extensive trade networks. Troy’s location near the Dardanelles strait made it a crucial hub for trade between the Aegean and the Near East. The city’s wealth and strategic position likely contributed to its prominence and its role in regional conflicts.

The Historical Context of Troy

The evidence gathered from Hisarlik and surrounding regions supports the idea that Troy was involved in conflicts during the late Bronze Age. Hittite texts refer to a city called Wilusa, which scholars believe is the Hittite name for Troy. These texts also mention a kingdom called Ahhiyawa, thought to be the Hittite term for the Mycenaean Greeks.

Correspondence between the Hittite king and the ruler of Wilusa indicates that Troy was a vassal state under Hittite influence but had interactions, sometimes hostile, with the Mycenaeans. This geopolitical context aligns with the narrative of a prolonged conflict between Greek and Trojan forces, as described in “The Iliad.”

The Legacy of Troy

The discovery of Troy has had a profound impact on both archaeology and our understanding of ancient history. It has shown that legends and myths often have roots in historical events and places. The meticulous work of archaeologists over the past century and a half has transformed Troy from a mythical city into a real, tangible site with a rich and complex history.

Today, Hisarlik is recognized as one of the most important archaeological sites in the world. The remains of ancient Troy attract scholars and tourists alike, eager to explore the city that once stood at the crossroads of myth and history. The story of Troy continues to captivate our imagination, reminding us of the enduring power of human curiosity and the quest for knowledge.