A pandemic is a disease that affects almost the entire population of a region or continent, usually in a short time. If we look back into history, humanity has faced several pandemics that, after killing tens of millions, have finally disappeared.

How did history’s worst pandemics finally ended?

The oldest pandemics have disappeared on their own, after wreaking havoc on the population. Over time, advances in medicine, improved hygiene and public health programs have managed to stop the spread of many infectious diseases, notes history.com.

Justinian’s plague: Has it disappeared by itself?

The first pandemic in history was caused by Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague, a highly contagious infectious disease. Three of the deadliest pandemics in history have been caused by this bacterium. Yersinia pestis infects some animals, especially rodents, and is transmitted to humans by the bite of infected fleas.

The Plague of Justinian arrived in Constantinople in 541 AD. It was carried over the Mediterranean Sea from Egypt by a recently conquered land paying tribute to Emperor Justinian in grain. The plague decimated Constantinople and spread rapidly across Europe, Asia, North Africa and Arabia killing between 30 to 50 million people, according to modern historians. Although the number of victims is impossible to determine with accuracy, many historians estimate that Justinian’s Plague killed almost 50% of the entire population of the planet at that time.

This first plague pandemic periodically hit several areas of the Old World and disappeared in the middle of the eighth century, most likely on its own, given that people did not understand how the disease was transmitted and could not take any action in order to stop it, in addition to trying to avoid the sick.

Black Death: The Invention of Quarantine

The second plague pandemic, caused by the same bacterium, Yersinia pestis, hit Europe in 1347. The disease reached the port of Messina in Sicily, carried by a Genoese ship from the city of Caffa, a Genoese colony in Crimea. From here, the plague spread like wildfire throughout Europe. In just four years, about a third of the continent’s population has been killed by the disease.

This time too, people did not know how the disease was transmitted, but they understood that it was contagious. Authorities in Venetian-controlled port city of Ragusa (now Dubrovnik), decided to keep newly arrived sailors in isolation for 30 days until they could prove they weren’t sick. Subsequently, the Venetians increased the period of forced isolation to 40 days (quarantino), the origin of the word quarantine.

This measure, which is still practiced during epidemics, probably helped to stop the first plague on Medieval Europe. Subsequently, the plague reappeared regularly until the end of the 15th century, then more and more rarely until the 19th century.

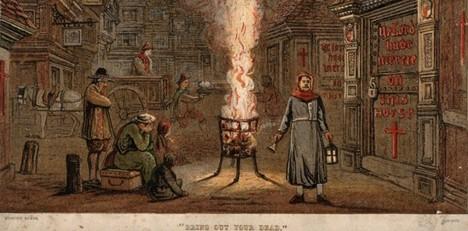

The Great Plague of London—Sealing Up the Sick

The last great plague epidemic that hit England took place between 1665-1666. The plague was already wreaking havoc on the mainland, so the British imposed quarantine on sailors coming from the affected ports. However, this measure was not enough. The bacterium was most likely carried from the Netherlands. The epidemic broke out in England in the spring of 1665. In just 18 months, the epidemic killed 100,000 people, about a quarter of London’s population at the time.

As the aristocracy fled London, including King Charles II of England and his family, local authorities tried to take various measures to stop the spread of the plague. Although it was not known at the time how the plague was transmitted, animals were believed to carry the disease. So the authorities ordered the killing of all the dogs and cats in the city. This measure proved to be very uninspired, given that the plague was carried by the fleas on rats, and dogs and cats could control the spread of these rodents.

Other measures have proven to be a bit more inspiring. Authorities banned all public events and victims were forcibly shut into their homes. Red crosses were painted on their doors and at night carts collecting corpses passed by. The victims of the plague were buried in mass graves.

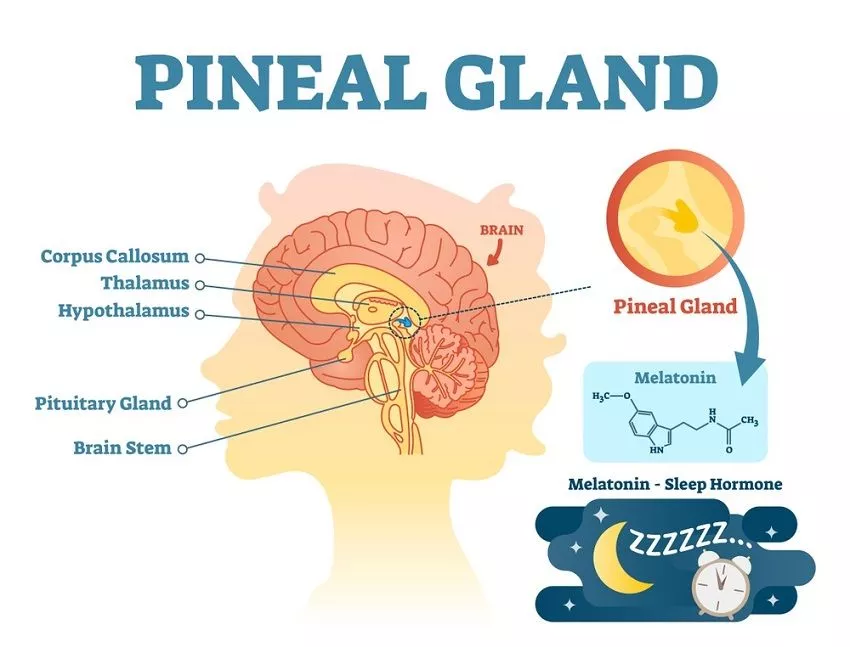

Smallpox: The invention of vaccination

Smallpox is a contagious disease caused by a virus. Although the plague caused some of the most frightening pandemics in history, smallpox was probably the most common infectious disease in history, with an estimated 250 million people killed in the 19th and the twentieth century alone.

The first attempts to vaccinate the population since the 18th century are related to this disease. The World Health Organization began a global vaccination campaign in the late 1960s. A decade later, smallpox became the first infectious disease to be completely eradicated. No cases have been reported since the late 1970s.

Cholera: Improving hygiene conditions through public health policies

The first cholera pandemic began in 1817 in the Indian region of Bengal. The disease that wreaked havoc in the nineteenth century, spreading rapidly throughout the planet. The plague is caused by a bacterium that particularly affects the small intestine. The bacterium is transmitted through water or food contaminated with feces.

The method of disease transmission was discovered by the British physician John Snow, who managed in 1854 to identify the source of the epidemic that was wreaking havoc in the Soho district of London: a public fountain on Broad Street. The closure of this water source led to the cessation of the epidemic.

John Snow’s discovery was the basis of many public health policies. The construction of modern sewage systems, access to drinking water and improved public hygiene have eradicated cholera in developed countries, but it’s still a persistent killer in third-world countries.