Over the centuries, the relationship between science and religion has ranged from open conflict to mutual dialogue. This complex interaction raises a fundamental question: can religion and science both be “right,” or are they irreconcilably at odds?

To explore this, we will journey through history’s key clashes and collaborations, examine how major faiths align (or clash) with scientific understanding, and consider insights from physics, biology, cosmology, and neuroscience.

We’ll hear voices of theologians, scientists, and philosophers on both sides – from those who see an unbridgeable chasm, to those who argue for harmony. In the process, we will analyze core concepts like faith vs. evidence, the realm of metaphysics, and the limits of scientific inquiry.

By the end, we hope to present a thoughtful perspective on whether reconciliation between science and religion is possible or desirable.

A Historical View: Conflict and Cooperation

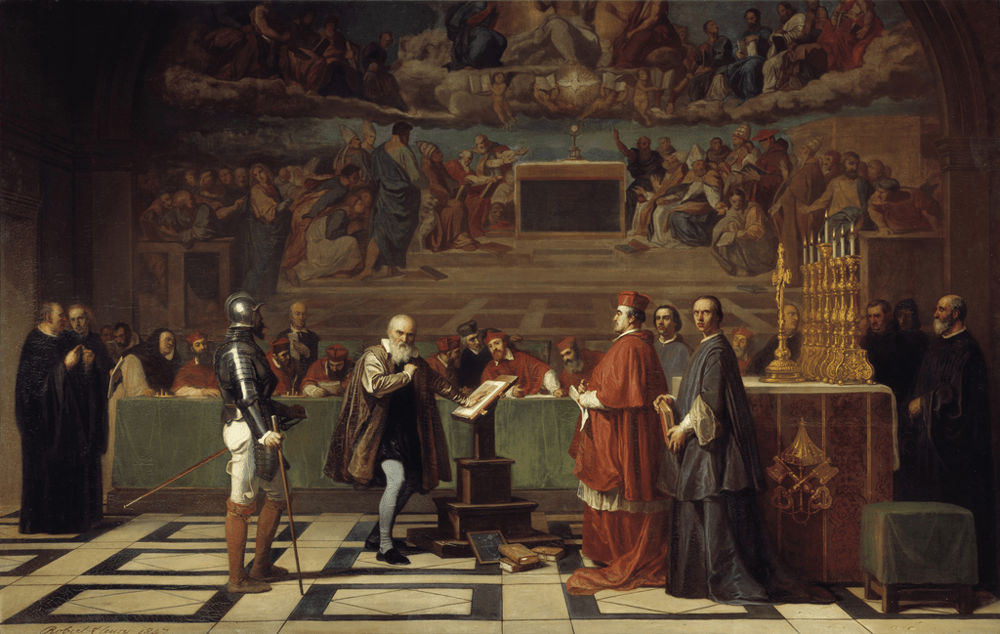

Galileo Galilei facing the Roman Inquisition in 1633 for advocating heliocentrism, a defining moment in science-religion conflict.

The history of science and religion is often highlighted by moments of conflict – but also instances of cooperation. A famous flashpoint was the Galileo affair of the 17th century, when astronomer Galileo Galilei was tried and condemned by the Catholic Church for teaching that the Earth revolves around the Sun.

Heliocentrism had been deemed “formally heretical,” and Galileo spent the rest of his life under house arrest for defying scriptural geocentrism. Similarly, in the 19th century, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection sparked religious controversy.

Many saw evolution as contradicting the biblical creation of humans, leading to heated debates and events like the Scopes “Monkey Trial” of 1925 over teaching evolution in schools. These episodes cemented a popular image of eternal “warfare” between science and faith.

However, the conflict narrative is only part of the story. Historically, cooperation and interplay have also been significant. Most scientific and technical innovations before the modern scientific revolution occurred in deeply religious societies.

Medieval Islamic civilization, for example, was a powerhouse of science: Muslim scholars pioneered algebra, optics, and medicine, driven by a view that studying nature was a way to understand the signs of God.

In medieval Christendom, many clerics and monks were also scientists – Roger Bacon, a 13th-century friar, helped formalize the scientific method. The Church funded universities and preserved knowledge through the Dark Ages, and figures like Gregor Mendel (the father of genetics) were themselves clergy.

Far from universally hostile, religion at times provided an intellectual framework and moral motivation for scientific inquiry. As one historian put it, the notion of an absolute, perennial “war” between science and religion is largely a myth – a 19th-century exaggeration now debunked by modern scholarship.

Indeed, many scientists were devout believers and saw no contradiction in their work and faith. Isaac Newton studied Scripture as deeply as physics. Galileo, a devout Catholic, famously wrote that the Bible teaches “how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go”, suggesting that religious truth and scientific truth operate in different domains.

In the 20th century, the astronomer Georges Lemaître was a Catholic priest who proposed the Big Bang theory – and even cautioned the Pope not to use it as proof of creation, to keep science and theology in proper perspective.

Clearly, the historical picture is nuanced: while specific doctrinal claims have clashed with scientific findings, there has also been fruitful dialogue. Religion and science have been characterized variously as antagonists, strangers, or partners, depending on the era and the issue at hand.

Major World Religions and Scientific Worldviews

Religion is not a monolith. Different faith traditions have developed their own stances toward scientific inquiry. Let’s look at how four major world religions – Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism – relate to modern science in terms of worldview, conflicts, and potential alignment.

Christianity and Science

Christianity has arguably experienced some of the most well-known science-religion tensions in the West. Beyond the Galileo episode, the debate over evolution has been a central point of discord.

Certain Christian groups, particularly biblical literalists or young-Earth creationists, reject evolution by natural selection – especially the evolution of humans – as incompatible with the divine creation story in Genesis. This fueled famous conflicts such as the Scopes Trial and continues in debates over school curricula.

Even today, some surveys find a portion of Americans (often Christians) disbelieve human evolution, influenced by their religious convictions.

On the other hand, many Christian denominations have made peace with science. The Catholic Church, for example, now explicitly accepts that evolutionary theory and Big Bang cosmology do not contradict belief in God.

As Pope John Paul II articulated, “truth cannot contradict truth” – if science and faith are both seeking truth, they must ultimately be reconcilablenewadvent.orgnewadvent.org. In 2008 the U.S. National Academy of Sciences even noted that the evidence for evolution can be “fully compatible with religious faith,” a view officially endorsed by numerous Christian (and other) religious bodies.

This reflects a widespread theistic evolution stance: the idea that God works through evolution and natural laws. Major Protestant denominations (like Anglicans and Lutherans), as well as the Catholic Church, largely hold this view, seeing no conflict between accepting science and affirming a Creator.

Christianity’s internal spectrum ranges from fundamentalist rejection of scientific findings to sophisticated theological integration. Historically, figures like St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas advised against rigid interpretations of Scripture on natural matters, urging that if a biblical text seemingly contradicts clear reason or evidence, it may need re-interpretation.

This “Handmaiden” tradition treated secular knowledge (science) as a helpful handmaid to theology. It motivated countless Christians to study nature as God’s creation operating by consistent laws – an idea that underpinned the rise of science in Europe.

Today, many Christian thinkers emphasize that science answers the “how” questions while religion addresses the “why” – for example, explaining natural processes vs. providing moral guidance or ultimate purpose. In practice, Christian responses to science range from conflict to accommodation, but a large contingent sees faith and reason as complementary.

Islam and Science

In Islam, science and religion have a rich intertwined history. During the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 14th centuries), Muslim scholars avidly pursued astronomy, medicine, mathematics, and more, often under the patronage of religious caliphs.

Their work preserved and expanded upon Greek science, and this knowledge later flowed into Europe. This flourishing was no accident: Islamic theology traditionally holds that studying nature is a way to appreciate the unity and wisdom of Allah.

The Qur’an encourages reflection on the natural world, seen as full of signs (ayat) pointing to God. Thus, far from opposing inquiry, classical Islam sacralized it – nature was an integral part of the Islamic worldview, and uncovering its laws was a pious endeavor. Notably, the 11th-century Arab polymath Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) formulated early scientific methods, insisting that hypotheses be tested by experiments – a very modern attitude.

In the contemporary Muslim world, attitudes toward science remain generally positive, though areas of tension exist. Many Muslims today say Islam and science are fundamentally compatible, seeing no contradiction in principle.

Scientific achievements in fields like medicine or engineering are often celebrated as part of the community’s progress. However, evolution has been one notable sticking point.

Some Muslim thinkers and schools do accept evolutionary theory (especially for non-human life), sometimes interpreting Adam and Eve in metaphorical or special terms. But others view human evolution as conflicting with Quranic accounts of human origins.

Pew Research interviews in Muslim-majority countries found that while most Muslims saw no general conflict with science, human evolution was a frequent point of friction. This mirrors debates among conservative Christians.

Additionally, questions like the age of the universe or origin of life can pose challenges if a literal reading of scripture is assumed. That said, Islam has no centralized authority defining doctrine for all believers, so views vary widely.

Countries such as Turkey or Pakistan have seen creationist movements, whereas other Muslim scholars actively seek theological frameworks that accommodate evolution and modern cosmology within an Islamic context.

Overall, Islam’s ethos that “knowledge is part of faith” still holds significant sway, and many Muslims echo the sentiment that studying science is a way to better understand God’s creation – provided that scientific findings are not used to undermine core religious truths like the role of a Creator.

Hinduism and Science

Hinduism presents a very different religious worldview – one that is pluralistic, richly philosophical, and comfortable with multiple levels of understanding. As such, Hinduism has not experienced the same stark clashes with science over specific theories.

Many Hindus perceive science and religion as overlapping spheres that ultimately search for truth. In fact, Hindu thought has long interwoven natural philosophy with spirituality.

Ancient Hindu scholars made advances in mathematics (originating the concept of zero and decimal notation) and astronomy. The lines between “objective science” and “spiritual knowledge” were often blurred; Hindu scriptures sometimes read like cosmological treatises.

There is a saying that many Hindu scriptures are also ancient scientific manuals, and vice versa. For example, texts like the Surya Siddhanta detailed astronomical calculations, and Ayurveda texts combined empirical healing arts with spiritual concepts.

When it comes to modern scientific ideas, Hindus generally show a high degree of flexibility. The concept of a cyclic universe (cosmic cycles of creation and dissolution spanning billions of years) is embedded in Hindu cosmology, which intriguingly resonates with the scientific timescale of a 13.8-billion-year-old universe, though arrived at independently.

On the topic of evolution, many Hindus see little conflict. In fact, some Hindu thinkers have claimed that evolutionary notions exist in Hindu thought – pointing out, for instance, that the ten avatars of Vishnu in mythology progress from fish to amphibian to mammal to human form, somewhat analogous to an evolutionary sequence.

Historical accounts show that after Darwin’s ideas became known in India, some Hindus eagerly drew parallels between the theory of evolution and their own doctrines. By the late 19th century, educated Hindus were often integrating Darwinian evolution with Hindu philosophy, suggesting that Vedic teachings anticipated evolutionary ideas.

Schools of Hindu philosophy such as Samkhya were comfortable with the idea that life develops through natural processes – their debate was less about whether evolution happens and more about whether there is a divine agency behind it.

In Hinduism, there is also a tradition of rational inquiry (Nyaya) and logic as means to obtain knowledge. This tradition valorizes reason and evidence, which aligns with the scientific spirit. Because Hinduism lacks a single creed or a literalist scripture that must be uniformly upheld, it has the agility to reinterpret teachings metaphorically.

For example, questions about the age of the Earth or origin of humans can be accommodated through non-literal readings of Hindu epics and Puranas. Many Hindus would agree with the statement that science reveals the mechanisms of the universe while their religion addresses moral and spiritual truths.

Surveys indicate that Hindu interviewees often view science and religion as naturally intertwined, even claiming that Hindu texts anticipated certain scientific findings (like the antiseptic property of turmeric or the concept of atomism).

While not all such claims are historically verifiable, they illustrate a general pride that Hindu tradition is not at odds with scientific discovery. In sum, Hinduism tends toward a synthesis approach – readily absorbing new knowledge into its expansive philosophical outlook.

Buddhism and Science

Among world religions, Buddhism is frequently regarded as especially compatible with science. It is a non-theistic tradition (traditional Buddhism does not posit a creator God), focused more on personal enlightenment and the nature of mind.

Many modern commentators, including the Dalai Lama himself, have drawn parallels between Buddhist practices and scientific methodology. Buddhism encourages an “impartial investigation of nature” (known as dhamma-vicaya in the Pali Canon) – essentially an empirical attitude applied to one’s own experience of the mind and reality.

The Buddha’s teachings often emphasize cause and effect (karma can be seen as an ethical cause-and-effect), mirroring science’s search for causal laws. Furthermore, Buddhism does not rely on divine revelation; it invites individuals to test the teachings in their own experience, akin to an experiment. This has led many to call Buddhism a “science of the mind.”

In terms of worldview, Buddhism doesn’t provide a detailed creation story or strict dogma about the material world’s origins. This absence of a Genesis-type narrative means there is little doctrinal basis for conflict with modern cosmology or evolutionary biology.

Indeed, Buddhist thinkers generally have no quarrel with the theory of evolution – nothing in core Buddhist doctrine says humans were created in their present form or that the Earth is young.

When Pew researchers interviewed Buddhists, they often described science and religion as separate and unrelated spheres, with science dealing with observable phenomena and Buddhism dealing with ethical living. They reported essentially no points of conflict with scientific topics like evolution.

Notably, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, has been an enthusiastic participant in dialogues with scientists, especially in fields like neuroscience. The Dalai Lama has stated a principle that astonishes some traditionalists: if solid scientific evidence conclusively disproves a claim in Buddhism, then Buddhism should relinquish that claim.

In his book The Universe in a Single Atom, he wrote, “If scientific analysis were conclusively to demonstrate certain claims in Buddhism to be false, then we must accept the findings of science and abandon those claims.”. This open-minded stance encapsulates why many see Buddhism as highly compatible with science – its emphasis is on understanding reality through observation and meditation, and it has a built-in flexibility to update or reinterpret teachings.

That said, Buddhism and science are not identical. Buddhism deals heavily in metaphysics and ethics – concepts like reincarnation, karma, and the pursuit of enlightenment lie outside the empirical scope of science.

Yet, some neuroscientists are studying Buddhist meditators to understand consciousness, and Buddhist ideas about the mind have influenced psychological therapies in the West.

The common ground is the exploration of the mind and alleviation of suffering – topics where Buddhism’s introspective techniques complement scientific brain research.

By and large, Buddhism exemplifies a religion that rarely clashes with science’s content, and often welcomes it. Many Buddhists view science as a partner that can help explain the how of the natural world, while Buddhism addresses the how to live and the inner transformation of the person.

Science, Faith, and the Big Questions: Key Disciplines

It’s one thing to speak of “science” and “religion” in general. But concrete points of dialogue or dispute often emerge in specific scientific disciplines. Let’s examine a few major fields – physics (and cosmology), biology (evolution), and neuroscience – to see how each has challenged and enriched religious perspectives.

Physics and Cosmology: Origins and the Universe’s Laws

Modern physics and cosmology probe deep questions that naturally interest religion: How did the universe begin? Why do the laws of nature exist as they do? For centuries, religious cosmologies provided the primary answers – creation stories of a universe crafted by God or gods.

Now, science offers its own grand narrative: a universe that began 13.8 billion years ago in a Big Bang and evolved to its current state through natural laws. To some believers, the Big Bang theory sounded eerily like the moment of creation – indeed the term “Big Bang” was coined by a skeptic of the idea, partly because it implied a beginning in time.

Ironically, the theory was proposed by Georges Lemaître, a Belgian priest-physicist, illustrating how science and religion can intersect. While most mainstream religious groups quickly accepted the Big Bang (seeing it as compatible with a Creator who initiated it), there have been debates on how literally to take the six-day creation in Genesis, for example.

Today, virtually all churches (except some creationist groups) accept the Big Bang model, often interpreting “days” metaphorically or seeing scripture as not intended to teach science.

Physics also raises the tantalizing “fine-tuning” issue: the physical constants of the universe (like the strength of gravity, electromagnetic force, etc.) seem precisely set to allow the existence of atoms, stars, and life. Some theologians and scientists have argued this is evidence of a cosmic Designer – a deliberate fine-tuning by God.

Others propose that if there are countless universes (the multiverse theory), we simply find ourselves in one of the rare universes that happened to be life-friendly, so no design is needed. The origin of the laws of nature themselves is another mystery: science can describe how the universe behaves, but why these laws exist at all (and not some chaotic mess) is a philosophical question that naturally invites religious contemplation.

As Albert Einstein once commented, “The eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility” – the fact that nature follows order and logic. Many religious thinkers take that orderliness as evidence of a rational mind behind the cosmos (logos).

On the flip side, physics has sometimes challenged religious assumptions. Classical Newtonian physics depicted a clockwork deterministic universe; some found this compatible with a law-giving God, while others worried it left no room for miracles or free will.

In the 20th century, quantum mechanics upended the picture with randomness and uncertainty at fundamental levels. Some spiritual writers seized on quantum indeterminacy to suggest space for human free will or even consciousness influencing reality – though most physicists caution that these interpretations are speculative.

And while relativity and quantum physics revolutionized science, they did not clash with religion in the way biology did; rather, they generated new philosophical discussions (e.g. the nature of time, which theology also grapples with regarding God’s eternity).

Cosmology’s findings – an ancient universe, Earth as a tiny speck, humanity emerging late in cosmic history – have sometimes been seen as dethroning humanity from the center of creation, which can challenge anthropocentric religious views.

Yet many theologies have adapted, seeing the vastness of space as expanding the grandeur of God’s creation. Notably, when the Pope in 1951 tried to claim the Big Bang supported the doctrine of creation, Lemaître gently corrected him: science should remain neutral on theological implications. In summary, physics and cosmology intersect with religion on questions of origin, design, and the nature of reality, producing both fascinating consonances (like the universe’s beginning) and areas where interpretations diverge.

Biology and Evolution: Life’s Diversity and Purpose

Perhaps no scientific idea has provoked religious debate as sharply as evolutionary biology.

Before Darwin, virtually every religion had an explanation for life’s diversity – typically, a creator deity fashioned various life forms in essentially their present state. Darwin’s 1859 On the Origin of Species proposed that all living beings are related through common ancestry, shaped by natural processes (mutation and natural selection) over immense time.

This evolutionary view of life initially shocked Victorian society and was resisted by some churches as undermining the special creation of humans. A famous early exchange was the 1860 Oxford debate where biologist T.H. Huxley (a champion of evolution) sparred with Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, illustrating the science-faith divide in stark terms.

In the time since, biology has amassed overwhelming evidence for evolution – from the fossil record to genetics. How have religions responded? We’ve already touched on Christianity’s range: some Protestant evangelical groups still uphold creationism (believing the Earth is only ~6-10,000 years old and species are fixed, created kinds), whereas Catholicism and most mainstream Protestant denominations accept evolution, viewing it as the mechanism by which God brings about life’s plan.

Islam likewise has both creationist voices and those who accept evolution (often excluding human evolution from acceptance). Hinduism and Buddhism have generally had little issue with evolution; Hindu thought even posited forms of progressive development, and Buddhist philosophy easily accommodates an ever-changing life process.

The crux of the conflict lies in what evolution implies: If humans arose from earlier animals through a blind process, what does that mean for the idea that humans are created “in the image of God” or have a special soul? If suffering and death (extinction) are natural tools of evolution, some ask why a loving God would choose such a painful method of creation. Theologians have grappled with these questions, proposing that evolution could be God’s way of endowing creation with freedom and self-coherence.

Some, like John Polkinghorne (physicist-turned-priest) and Teilhard de Chardin (a Jesuit paleontologist), argue that evolution has a spiritual dimension or direction guided by God, even if subtly. Others accept the science fully but interpret the religious texts in non-literal ways (e.g. Adam and Eve as metaphorical).

From the scientific perspective, evolutionary theory is firmly based on evidence and experiment, and it does not invoke supernatural intervention. Biologists like Richard Dawkins assert that the undirected, trial-and-error process of evolution makes the idea of a designer unnecessary – even proclaiming that Darwin made it possible to be an “intellectually fulfilled atheist.”

Dawkins and his peers argue that complex life can arise from simple beginnings through natural law, undermining the traditional argument from design. They also note that certain features of life (like the blind spot in our eyes or the recurrent laryngeal nerve in giraffes) are clumsy outcomes of evolution, not what one might expect from an optimal intelligent design.

Despite these arguments, many religious individuals manage to embrace evolution without abandoning faith. They might say that evolution is the how and God is the why – evolution describes the process, while God imbues it with purpose or sustains its laws. The field of evolutionary creationism (or theistic evolution) is populated by scientists who are also believers, such as geneticist Francis Collins (director of the Human Genome Project).

Collins, an evangelical Christian, famously wrote The Language of God, where he calls DNA “God’s language” and sees the elegance of biology as reflective of God’s creative genius.

Similarly, biologist Kenneth R. Miller, a Catholic, has been a vocal defender that one can accept Darwinian evolution and remain a person of faith. These voices argue that there is no inherent contradiction – one can view evolution as the tool God used to bring about the rich tapestry of life.

In sum, evolutionary biology tested religious interpretations in profound ways, forcing a re-examination of how to read sacred texts and understand humanity’s place. It led to polarized responses: conflict (as seen in creationist movements and religiously-fueled opposition to teaching evolution) and integration (as seen in the many religious thinkers who found ways to accommodate or even celebrate evolution as part of God’s plan).

The question “Can religion and science both be right?” is sharply felt here – can the biblical story of creation and Darwin’s story of evolution both carry truth? Many conclude they can, if we recognize the different genres and purposes of scripture versus science. Scripture, they say, teaches spiritual truth (the why of creation – that it is ultimately from God and has meaning), while science teaches the material how.

Those who hold this view point to the statement by the National Academy of Sciences that accepting evolution is fully compatible with believing in God. However, others, like Dawkins, maintain that religious explanations are unnecessary or false in light of evolution, illustrating how the debate remains lively.

Neuroscience and the Soul: Mind, Brain, and Belief

Advances in neuroscience – the study of the brain and nervous system – have opened another frontier in the science-religion dialogue. Traditionally, most religions hold that humans have an immaterial soul or mind distinct from the purely physical body.

Free will, moral reasoning, and religious experiences have been seen as reflections of this spiritual soul. Neuroscience doesn’t explicitly set out to refute the soul, but its findings increasingly suggest that our mental life is rooted in brain activity.

This poses challenging questions: If every thought, emotion, or spiritual experience correlates with neural firings in the brain, what room is left for an independent soul? Are we “more than matter,” or, as Francis Crick provocatively put it, “You’re nothing but a pack of neurons”?

Modern brain imaging has shown that religious experiences have identifiable neural correlates. For example, in studies of neurotheology, researchers like Dr. Andrew Newberg have scanned the brains of Buddhist monks in meditation and Franciscan nuns in prayer.

Remarkably, they found measurable patterns of brain activity corresponding to transcendent experiences – such as reduced activity in the brain’s orientation area during deep meditation, which might relate to the feeling of “oneness” with the universe.

To a scientist, this suggests that even our loftiest spiritual states are embodied in neural processes. To a religious person, this could simply be the mechanism through which God or the spiritual dimension interacts with us. But it does remove some of the mystery: mystical experiences can be stimulated, at least in part, by electrodes or drugs that act on the brain, hinting that the sense of encountering the divine might have a biological basis.

Neuroscience has also weighed in on free will – with experiments showing that our brains may initiate decisions fractions of a second before we become consciously aware of them. Such findings raise age-old questions that religions have grappled with: Do we have a soul making choices, or are our choices determined by brain chemistry (or by divine predestination, as some theological doctrines hold)? The science doesn’t settle the philosophical question of free will, but it challenges simplistic views of a totally “free” inner self.

Another area is the nature of consciousness. Consciousness – the fact we have subjective experience – is still a great mystery for science. Some argue it’s an emergent property of complex brains; others wonder if it hints at something beyond the material (which could align with religious ideas of a soul or universal consciousness).

Here, interestingly, some scientists and religious thinkers find common ground in admitting we don’t yet understand consciousness fully. It might be one of those “limits of scientific inquiry” where metaphysical or spiritual perspectives still have a say, at least until science can explain it better.

Crucially, neuroscience findings have ethical and existential implications for religion. If personality and morality can be drastically changed by a brain tumor or injury (as cases show), that suggests our “self” is tightly tied to our physical brain. What, then, of an immortal soul?

If degenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s can strip away memory and personality, how do we conceive of the soul’s continuity? Some theologians respond that the soul might work through the brain (so damage to the brain is like damage to an instrument, not the loss of the soul itself).

Others see the neuroscience perspective as a wake-up call to refine doctrines of soul – perhaps moving away from a dualistic “ghost in the machine” view to one where soul and body are more integrated (as in Christian resurrection theology, which emphasizes an embodied soul).

Neuroscience has also delved into why humans believe. Evolutionary psychology and brain science suggest that belief in gods or spirits could have natural explanations – maybe byproducts of our cognitive wiring (e.g. the tendency to infer agents behind events, useful for survival, can lead to belief in invisible agents like deities).

Some studies indicate that religious belief or spiritual practice can have positive effects on mental health, which religious people might say is evidence of tapping into a spiritual reality, while a skeptic might say it’s simply psychology.

All told, neuroscience often places religion under the lens of analysis: faith becomes something the brain does. This can feel reducing to believers – turning the soul into synapses.

Yet, it’s also an opportunity for deeper understanding. For instance, knowing the brain basis of compassion or meditation doesn’t negate the value of those practices; rather, it shows a unity between our spiritual aspirations and our biological nature. Many religious individuals in fields like counseling or pastoral care welcome insights from brain science to help people (for example, using knowledge of brain chemistry in treating depression, rather than seeing it purely as a spiritual failing).

So, can religion and science both be right when it comes to the mind and soul? It depends on the framing. If a religion insists on a literal, separable soul-entity completely independent of the brain, neuroscience evidence challenges that. But if one views the soul in more poetic or holistic terms – as the seat of identity and relationship with the divine, which operates in tandem with the physical brain – then there is room for synthesis.

Some theologians argue that neuroscience is uncovering how God designed the brain to mediate spiritual experiences. Others, like secular scientists, conclude that neuroscience shows we don’t need the soul hypothesis at all. This area remains one of active and fascinating dialogue, touching on what it means to be human at the deepest level.

Perspectives: Conflict, Compatibility, and Everything in Between

Throughout this journey, it’s clear that the “religion vs. science” debate is not one-sided. There are passionate advocates on both ends – those who see an inevitable conflict and those who see potential harmony. Here we present a few influential perspectives that highlight the spectrum:

The New Atheist Argument (Conflict): In the 21st century, voices like biologist Richard Dawkins, neuroscientist Sam Harris, and the late writers Christopher Hitchens and Victor J. Stenger have argued that science and religion are fundamentally incompatible.

Dawkins has flatly stated, “I see the scientific view of the world as incompatible with religion”. He and others reason that science relies on evidence, skepticism, and natural explanations, whereas religion often requires belief in miracles and supernaturals without evidence.

Dawkins famously described faith as “belief in spite of, even perhaps because of, the lack of evidence” – essentially calling faith an evasion of the need to think critically. In his view, religion is a “cop-out” that teaches people to be satisfied with mystery rather than seeking real understanding.

Another New Atheist, Sam Harris, has likened religious faith to a kind of widespread delusion, and criticized moderate religion for providing cover to fundamentalism. These thinkers point to historical wrongs (like persecution of scientists, or opposition to medical advances) and current issues (such as denial of climate change or evolution by some religious groups) as evidence that when religion makes factual claims, it gets things wrong and impedes progress. For them, science is the only credible way to knowledge, and religion’s claims – from creation to miracles to an afterlife – are not supported by evidence and thus should be rejected.

They advocate for a worldview of scientific skepticism and secular ethics, arguing that moral values do not require religion and can be derived from an understanding of human well-being.

In summary, the conflict position asserts that while individuals might personally reconcile science and faith, in an intellectual sense every explanation that religion traditionally offered has been or will be supplanted by science (or admitted as unanswerable), leaving no domain in which religion can still claim knowledge.

As physicist Steven Weinberg once put it, “The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless” – reflecting a view that science doesn’t find any inherent cosmic purpose, undermining religious narratives of meaning. New Atheists don’t just see incompatibility; they often see religion as harmful to society’s advancement, a viewpoint encapsulated in Hitchens’ blunt claim that “Religion poisons everything.”

Religious Compatibilism (Harmony): In stark contrast, many theologians and scientists advocate that science and religion can not only coexist but enrich each other.

A famous model is Stephen Jay Gould’s idea of Non-Overlapping Magisteria (NOMA): science and religion occupy separate “magisteria” or domains of teaching authority.

According to Gould, science covers the empirical realm – what the universe is made of and how it works – while religion deals with questions of ultimate meaning, purpose, and moral value. “Science can only ascertain what is, not what should be,” observed Albert Einstein, “and outside of its domain value judgments remain necessary. Religion deals with evaluations of human thought and action”.

From this standpoint, there is no conflict if each stays to its expertise. Conflict arises only when one side strays: for example, a religion insisting on scientific facts (e.g. a 6,000-year-old Earth) or scientists proclaiming on moral truths based solely on data.

Gould and Einstein both argued that such conflicts are a result of category mistakes – religion mistakenly acting as primitive science, or science attempting to derive meaning from facts alone. The solution they propose is a respectful dialogue where science informs us about the natural world, and religion (or philosophy) informs us about ethical values and spiritual meaning.

Other thinkers go further, suggesting an active synergy. The physicist-turned-Anglican priest John Polkinghorne wrote that science and religion are friends because both seek truth about reality – science about its material aspect, religion about its ultimate grounding. He sees them as answering different questions that complement each other, like two maps of the same reality (one map of physical terrain, one of human meaning).

The geneticist Francis Collins is another prominent example: as a devout Christian and scientist, he describes experiencing the awe of scientific discovery as an act of worship, revealing the intricacy of God’s creation.

Collins and others in the Religious (or Theistic) Naturalist camp maintain that embracing scientific findings need not diminish faith, but can deepen one’s appreciation of the divine. For instance, understanding genetics and evolution can inspire awe at the creative processes of life, which a believer can attribute to God’s genius.

There are also philosophers like Alvin Plantinga who have flipped the script on the conflict narrative. Plantinga argues that “there is superficial conflict but deep concord between science and theistic religion, and superficial concord but deep conflict between science and naturalism.”

In other words, he believes that on the surface science and religion might have some tensions (e.g. specific disagreements on evolution or miracles), but at a fundamental level, they are in harmony – since a rational God would create an orderly universe that science can study.

Meanwhile, he contends that a pure naturalistic worldview (denying any intelligence behind the universe) is on shaky ground because if our brains are just products of survival rather than truth-seeking, can we fully trust our rational faculties? Plantinga’s view is that science itself might be pointing beyond itself – toward a grounding in something like a divine mind.

Whether or not one agrees, this illustrates a sophisticated attempt to show compatibility at a philosophical depth.

Finally, there is the perspective of Religious Naturalism or Process Theology, where the boundary between science and religion blurs. Religious naturalists assert that nature (as understood by science) is the ultimate reality and is worthy of a religious response – wonder, reverence, gratitude.

They drop supernatural claims but retain a “religious” appreciation for the universe revealed by science. For example, a religious naturalist might feel spiritual transcendence contemplating the cosmos or the evolution of life, without invoking any deity separate from that cosmos.

This approach says both science and religion can be “right” if we redefine religion to be about finding meaning in the natural world as unveiled by science. It’s a kind of middle path where one doesn’t hold any belief that contradicts scientific evidence (so no conflict), but one still fulfills the human longing for purpose and connection by situating ourselves within the scientific story of the universe.

An example of this would be Ursula Goodenough, a biologist who wrote The Sacred Depths of Nature, describing a “planetary ethic” and sense of the sacred grounded in understanding biology and ecology. Similarly, Process theologians like Charles Hartshorne or John Cobb incorporate evolution and physics into their concept of God (viewing God not as a static omnipotent ruler but as the evolving life of the universe itself).

These nuanced positions demonstrate creative ways people have tried to reconcile the truths of science with the truths of human spiritual experience.

Middle Ground and Dialogue: Many people actually fall in a pragmatic middle ground. They may accept most of science but also hold religious beliefs, compartmentalizing the two or integrating them in personal ways.

For instance, a doctor might use only science in the clinic but still pray or find comfort in religion for existential questions. Societies and educational institutions increasingly encourage a dialogue model – bringing scientists and theologians together to discuss ethics (like how to use biotechnology responsibly) or philosophical questions (like consciousness or free will).

Even some atheist scientists acknowledge that science doesn’t address everything of human importance – as Einstein noted, science can describe facts but cannot make value judgments, and that is an area where philosophy or religion enters. Conversely, many religious leaders acknowledge that on matters of empirical fact – the age of Earth, the mechanism of disease – science has a far better track record and should be respected. This mutual humility is perhaps a key to future coexistence.

To illustrate, the Religious Naturalist Association describes it this way: “Religion and science complement each other, contributing things the other does not offer, but they can also conflict when religion makes claims about how things are that with the eyes of science seem impossible”.

For example, a literal belief in a virgin birth or a young Earth collides with biology and geology. Many moderate believers resolve this by seeing those religious narratives as symbolic rather than literal. Indeed, a large number of Jews and Christians today interpret Biblical miracles as metaphor or myth, fully accepting evolution and modern science in their worldview.

They often conceive of God in less interventionist ways – not a micromanager of nature who constantly violates natural laws, but as the ground of being or the author of laws, operating through natural processes. In such a view, there is no need to reject science; one simply understands religious scriptures on a different level (teaching moral or spiritual truths, not physics lessons).

On the opposite side of that middle ground, some skeptics concede that while science gives factual knowledge, humans seem to crave meaning and community in a way science alone doesn’t fulfill. This opens space for something like religion or spirituality, provided it doesn’t contradict evidence.

The late astronomer Carl Sagan, an ardent scientist, often spoke in quasi-spiritual terms about the cosmos (“starstuff contemplating the stars”), exemplifying a reverence for reality that, while secular, had the emotional tone of religious awe.

Faith, Evidence, and the Limits of Inquiry

A core issue underpinning the debate is the epistemology – how do religion and science claim to know things? Science is built on evidence, testing, and doubt. Religion often involves faith, trust in authority or revelation, and spiritual insight. Critics say these methods are at odds: faith, by one definition, is belief without evidence or in spite of evidence.

Defenders respond that religious faith is not blind but is supported by personal experience, historical testimony, or intuitive understanding of things like moral truth – forms of evidence, perhaps, just not the kind science uses. The phrase “leap of faith” acknowledges that religious belief isn’t strictly provable; it requires a commitment beyond what can be seen. Whether that is a virtue or a vice is hotly debated.

Metaphysics is another arena: Science deliberately limits itself to the natural world – what can be observed and measured. It does not speak to the existence of the supernatural; by method, it neither confirms nor denies it. Some argue that if something consistently interacts in the observable world (like purported miracles or answered prayers), then it should be detectable by science. If it’s not detectable, perhaps it has no effect – which would make it moot for our world.

Thus, hardline skeptics conclude that talk of the supernatural is meaningless. However, others point out that science has limits – there may be realities beyond the physical (like God, or abstract values) that are real in a philosophical sense but not empirically testable.

Does that mean science and religion are discussing entirely separate realms? This is essentially Gould’s NOMA idea again. For example, the existence of God is not a question science can answer with an experiment; it’s a metaphysical question. As such, one could be a rigorous scientist and still hold a belief in God as a metaphysical commitment. Many do.

The conflict arises if one claims scientific backing for God (like pointing to a gap in current scientific knowledge and saying “that’s where God acts”) – historically, these “God of the gaps” arguments have tended to shrink as science advances.

Another important distinction is descriptive vs. prescriptive. Science is superb at describing “what is”. It can tell us the age of the universe, how the brain works, what causes diseases, etc. But can it tell us “what matters” or “how we should live”? Einstein famously said, “Science can ascertain what is, but not what should be”.

Questions of meaning, purpose, and morality – the “why are we here?” and “how ought we to behave?” – lie outside pure scientific analysis. Religion (and philosophy) traditionally handle those.

A scientist can of course have ethical values, but they derive them from philosophical reasoning or humanistic concern, not from a petri dish. As an example, science can inform us that humans evolved traits like empathy because of social survival advantages, but it doesn’t tell us whether we ought to be empathetic or why cruelty is wrong in a moral sense.

That requires a framework beyond empirical facts. Many religious people argue this is where religion retains its vital role – providing a foundation for values and meaning that science by itself might struggle to supply.

Finally, consider the limits of human understanding. Both science and religion, at their best, are humble about what remains unknown. For scientists, every discovery opens new questions; some wonder if the human brain has inherent limits that might never comprehend a “theory of everything” or the true nature of consciousness.

For religion, the concept of mystery is central – finite minds grappling with an infinite reality. In a paradoxical way, acknowledging mystery is something science and religion share. The difference is in approach: science chips away at mystery, testable piece by piece, whereas religion might embrace certain mysteries as transcendent or not meant to be solved, but rather contemplated.

A thoughtful stance might be that both science and religion need each other’s sensibilities: science needs the ethical compass and humility that religion (at its best) can convey, and religion can benefit from the reality-check and curiosity that science embodies.

Toward Reconciliation or Further Divergence?

So, can religion and science both be right? The answer, as we’ve seen, is not a simple yes or no. It greatly depends on what we mean by “religion” and “science,” and in what domain we expect each to be “right.”

If we expect them to answer the same questions in the same way, conflict is almost guaranteed. A literalist religious approach that claims sacred texts as infallible science textbooks will clash with what empirical investigation reveals.

Conversely, a scientistic approach that insists only laboratory-verifiable statements are meaningful will dismiss much of what religion cares about. In these extreme forms, each effectively tries to cancel out the other – and indeed, history and current events give plenty of examples of such clashes.

Notably, vocal atheists and religious fundamentalists, despite being opponents, often agree on one thing: that science and religion are incompatible and one must choose sides.

Yet, many others find a middle path. They hold that science and religion speak different “languages” or address different dimensions of life. Science excels at explaining: it tells us how the world works with increasing precision.

Religion (and spirituality) excels at interpreting: it helps people find meaning, purpose, and moral orientation. In this view, both can be “right” within their proper realm – science is right about the age of the Earth, the equations of physics, the mechanism of disease, etc., while religion can be “right” about the importance of justice, love, compassion, and our relationship to something beyond the material.

They answer different questions and thus aren’t vying for the same prize. As one essay on the science-religion intersection put it, “Religion and science complement each other, contributing things the other does not offer”. From this standpoint, a reconciliation is not just possible but natural, once we stop expecting one to do the other’s job.

However, skeptics of reconciliation caution that even if religion focuses on meaning, it still often makes claims about reality (e.g. miracles, divine intervention, life after death) that do intersect with science.

And when it does, those claims need to face the same scrutiny as any other. In practice, many believers have adjusted their understanding – interpreting miracles metaphorically or as rare exceptions, and often seeing scientific discovery as revealing how God works rather than contradicting His existence.

A common stance among moderate religious thinkers is: Truth is one – so if something is scientifically true, it cannot ultimately undermine a true faith, because all truth comes from the same source (a sentiment expressed in the Catholic idea that truth cannot contradict truthnewadvent.org). This encourages a stance of integration – seeking a worldview where scientific knowledge and spiritual wisdom coexist coherently.

Is such a reconciliation desirable? For many, yes. The alternative – a world split into warring camps of fanatical religion and dogmatic scientism – is unsettling. Individuals who straddle the line (religious scientists, scientifically literate clergy, etc.) often act as bridge-builders, showing by example that one can appreciate the depth of both domains.

Interfaith and science-religion dialogues sponsored by organizations (like the Templeton Foundation or the Vatican Observatory) strive to foster mutual understanding. They tackle issues like environmental stewardship, where science provides data on climate change and religious ethics motivate care for creation, demonstrating a productive synergy.

On the other hand, some argue that a full reconciliation might dilute both realms. If religion bends too much to accommodate science, does it risk losing its distinctive claims and power to inspire? If science is overly lenient to religious perspectives, does it risk compromising its empirical rigor? These are valid concerns.

A certain creative tension may always exist, preventing either from overstepping. After all, humanity has managed to live with both rationality and spirituality for millennia; perhaps that dynamic interplay is itself essential.

In the end, the question might not be about either side “being right” in a winner-takes-all sense, but rather about different kinds of truth coexisting. We might consider the natural world as a book that science reads, and the realm of meaning and value as a book that religion (or philosophy and art) reads.

As long as we don’t confuse the genres, we can value both. The human experience seems to demand both explanation and meaning. Science, as the great explainer, gives us astonishing power and understanding – from curing diseases to exploring galaxies.

Religion, as a meaning-maker, provides context for those discoveries – urging us to use them wisely, to marvel with gratitude, or to seek comfort in the face of what remains unknown or uncontrollable (like mortality).

To return to the titular question: Can religion and science both be right? They certainly can both be wrong if misused – science divorced from morality, or religion denying reality, have led to horrors. But at their best, many would say yes, they can both be right – not in the same way, but in complementary ways. As Einstein – who was not conventionally religious but was deeply spiritual about the cosmos – wrote: “Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.”

In this aphorism, “religion” meant for him the sense of awe and ethical insight that must accompany our cold hard facts, and “science” meant the critical thinking that must inform our beliefs.

If we take it in that spirit, the ideal future is one where science and religion learn from each other: science keeps religion intellectually honest, and religion keeps science ethically and existentially mindful. Whether one identifies with a faith or not, this balanced approach could enrich the human pursuit of truth – uniting the empirical and the spiritual into a fuller understanding of reality. That may be the surest path to both wisdom and peace.

Sources:

Pew Research Center – “On the Intersection of Science and Religion” (2020)

Wikipedia – “Relationship between religion and science”

Wikipedia – “Galileo affair”

Catholicism Pure & Simple – “The Bible teaches us how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go”

Wikipedia – “Islam and science” (Islamic Golden Age and theology)

Wikipedia – “Hinduism and science”

Wikipedia – “Buddhism and science”

Wikipedia – “Christianity and science” (Augustine/Aquinas)

National Academy of Sciences – Science, Evolution and Creationism (2008)

Richard Dawkins, interview quote (1995) – Times Higher Education

Religious Naturalism website – “Science and Religion”

Alvin Plantinga’s thesis – Where the Conflict Really Lies (2011)

Albert Einstein – “Science and Religion” (1941 essay)

The Guardian – Einstein letter (2008)