The ancient history recorded, during the III-II centuries BC, three exhausting and bloody military conflicts (264-146 BC), for the supremacy in the western basin of the Mediterranean between Rome and Carthage (a Phoenician colony founded in 814 BC on the Coast of North Africa).

First Punic War ended with the defeat of the African metropolis, who gave up Sicily and paid a significant amount of money (3,200 silver talents) to the victors. Also, in 238 BC., Rome took advantage of the rebellion of Carthage’s mercenaries and occupied Sardinia and Corsica (islands of Carthaginian / Punic maritime empire).

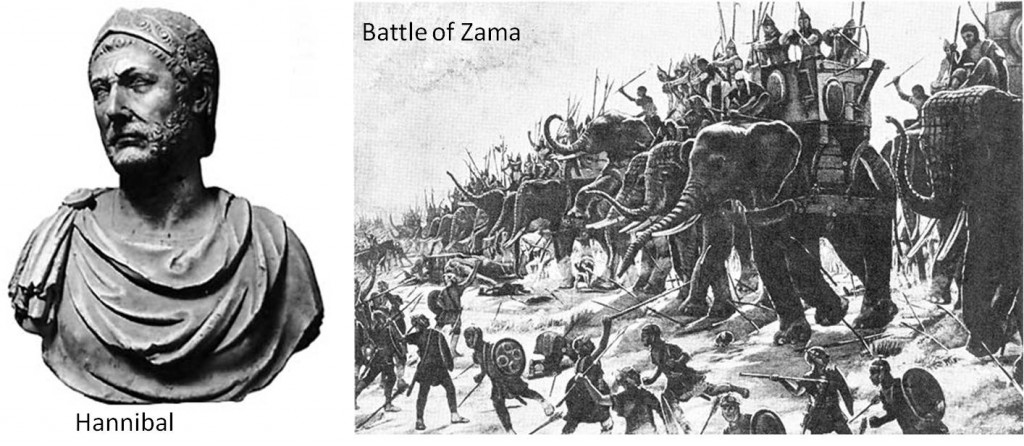

Hannibal digs up the hatchet

Years passed, but the animosities between the two cities were not forgotten, reaching their climax when the hatchet was unearthed by the carthaginian general, Hannibal, who was appointed commander of Carthaginian forces from Spain in 221 BC.

The new conflict, lengthy prepared by the ambitious Carthage, had as the main scene of military confrontation the Apennine Peninsula, but also took place on several secondary fronts in the Western Mediterranean, in Spain, Sicily, Northern Balkan Peninsula, North Africa.

The reasons of mediterranean chaos arise from the expansion tendency of the Punic metropolis in Spain for compensating the losses from the first dispute with the Romans (264-241 BC) and the desire for revenge against the Eternal City, instilled to Hannibal from an early age (9 years) by his father, Hamilcar, leader of Carthaginian army between 247-229 BC.

A consummate and absolute warrior

A consummate and absolute warrior

Hannibal, as described by historian Livy (Titus Livius):

“When he was facing dangers, he was the most intrepid of all and in the midst of dangers he always displayed the greatest sound mind. No effort exhausted him, neither bodily nor spiritually and nothing could take him down. It was by far one of the best riders and pedestrians. In any battle, he was always to start and the last one to withdrawn.”

This characterization reminds us of the one that Dio Cassius did on Decebalus:

“He was skilled in war and ingenious in deed, knowing when to invade and when to retreat on time, master in traps, mighty in battle, things for which he has always been a dreaded opponent for the Romans.”

Unlike the last king of Dacia, Hannibal was “was unparalleled cruel, a perfidy more than punic; for him, there was no truth, there was nothing holy; he had no fear of gods, didn’t observe any oath; he was disregarding any faith”.

The Carthaginians cross the Pyrenees and Alps

In 219 BC., Hannibal began a military campaign against the Iberian city of Saguntum, which was “by far the richest of cities across the Ebro” (alliance treaty with the Romans in 231 BC), that conquered after an eight-month siege. The Roman Senate declared war against Carthage (281 BC), accusing it as disregarded “the Ebro treaty”, signed in 226 BC by Hasdrubal, Hannibal’s uncle (the agreement was delimiting the spheres of influence in the Iberian Peninsula). In these conditions, after consolidating his dominion in Spain, Hannibal channeled his efforts for a daring expedition against the city of seven hills.

Hannibal had methodically planned the military campaign, which proved his experience in organizing and waging war: “as it was well-informed on the fruitfulness of the land of the Alps and around the Po (Padus) river, about the population of this land and especially about the audacity of men in war and their hatred against Romans”.

Although the Romans tried delaying the bold program of the Carthaginian by sending two armies (their destination: Spain and North Africa), Hannibal foiled their plans and started leading a hostile (50,000 pedestrians, 9,000 knights and 36 elephants) in the summer of 218 BC towards Italian lands.

After an arduous route (crossing the mountain ridges of Pyrenees and Alps, crossing the Rhone) and considerable human losses, the Carthaginian army reached the Po Valley (October 218 BC), Sparking panic among the residents. Historian Polybius notes: “the echo of the latest news on the Carthaginians in connection with the occupation of Sagunt had barely ceased and, as a consequence, the Romans had decided to send one of the consuls in Libya, to besiege Carthage itself, and the other consul in Iberia, to fight there against Hannibal, and here’s the news that Hannibal was in Italy with his army, besieging certain cities”. Although the marathon affected his military potential, Hannibal completed his troops with those of Celtic tribes, “who were seeking a propitious moment to leave the Romans.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9LtsbInpQqs

Panic takes over the Romans

In the Po Valley, a Roman army, led by consul Publius Cornelius Scipio and another army, under the command of T. Sempronius Longus, tried to banish Rome’s fears, but were defeated by the Carthaginians at Ticinus (November 218, BC) and Trebia (December 218 BC).

Livy wrote: “Rome was so terrified at the news of this defeat and the citizens thought that the Carthaginian army shall besiege the city immediately with no hope of receiving some help to remove this army from the gates and the walls of Rome”.

Insecurity and hasty decisions have affected Romans’ actions regarding their confrontations with the unwanted guests. The new Roman commander, Caius Flaminius, exasperated by Carthaginian’s audacity, didn’t wait the junction with the army of consul C. Servilius and started pursuing Hannibal.

Meanwhile, the African general entered into Etruria and sowed terror in the land between the town of Cortona and Lake Trasimene (Trasimenus) to determine Flaminius making mistakes.

Hannibal has meticulously prepared his success, placing the camp in a favorable place for an ambush, “exactly where Lake Trasimene is extended to the foothills of Cortona”. The land didn’t allow Romans to conduct their military forces, so they risked being blocked from all sides.

Disaster at Trasimenus (Trasimene)

Consul Flaminius, arrogant in statements but slouch at discovering the enemy’s tactics, was surprised by the Carthaginian troops at Lake Trasimennus (March 217 BC). Polybius presents us the battle: “In front of this unexpected appearance, Romans centurions and tribunes not only couldn’t run for help where needed, but they didn’t know what was happening, either because the fog did not allow them to see anything around, either because the enemies were coming down from the heights, bursting into many places. For in the same time, they were being attacked from front, rear and flank, so most of the army was shattered even marching, without being able to defend, like they have been betrayed by captain’s recklessly”.

The disaster at Trasimenus, where 15,000 Roman soldiers lost their lives – and only 2.500 Carthaginians – created a difficult situation for the citizens of Rome. The Romans elected Q. Fabius Maximus as dictator. Q. Fabius Maximus was known for his honesty and was careful to avoid the mistakes made by his predecessors. Due to this tactics, he was called Cunctator – the Retardant.

Rome was not only fighting with Hannibal, but also with itself, with the petty, paltry mentalities of some fellow citizens, eager to fame and power. Cunctator’s plan, to harass his opponent and to avoid extensive battles was threatened by Minicius Marcus’s appointment as commander of the cavalry, a supporter of immediate military action. Ignoring Fabius’s tactics, the impulsive Minicius started a battle with the Carthaginian forces (Gerunium), the intervention of his colleague being the only one to prevent a new military catastrophe for the Romans. Faced with lack of supplies and low morale of his troops because of unpaid solds, Hannibal turned his attention to the fertile land of Apulia (near the Adriatic) to rebuild the army.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HGlo6QowOIM

Hannibal sets his camp at Cannae

He set up camp near a village called Cannae, being separated from his pursuers by Aufidus River (today Ofanto, river in Apulia). Meanwhile, the Roman senate has expressed indignation towards the prudent policy of dictator Fabius (useful to stop the decline of the army) and decided the election of two commanders instead of predecessors: consuls C. Terentius Varro and L. Aemilius Paullus.

But the Romans have committed the same mistake (as at Trasmennus), as the army leadership level had different opinions on approaching the fight with Hannibal. Sure of victory, Varro dominated Rome by optimistic speeches, while Paullus, decently, assured that he “will not make hasty and premature decisions, as the circumstances dictate people making certain decisions and not vice versa”.

For the battle with Hannibal, that Romans hoped to be definitive, they mobilized eight legions (Total number: 80,000 footmen and 6,000 horsemen) which revealed their panic towards an eventual defeat. The Roman army started in pursuit of the enemy, which they reached near Aufidus river. Ignoring the advice of Paulus to avoid any accident with the Carthaginians until a right time to start the fight, Varro crossed his troops to the other side of the river, near the Punic (Carthaginian) army. Paullus followed him, although he expressed distrust in its tactics.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQNCGqfjaBc

A brilliant strategy

The Roman troops were arranged as follows: on the right wing – the Roman riders (led by Paullus); in the middle – allied infantry and the Roman legions (commanded by Geminius Servilius) and on the left side – the Allied cavalry (commander: Terentius).

In front of the Romans were 40,000 footmen and 10,000 horsemen arranged by Hannibal in a battle line (as a crescent, with the round shape directed toward the opponent): in the left – Iberian and Celtic horsemen, led by Hasdrubal; in the center – Libyan infantry, under the command of Hannibal; in the right – elected riders, led by Maharbal.

On August 2, 216 BC, was starting the Battle of Cannae, which has assured Hannibal’s fame. The layout of the Punic troops in a crescent shape was a trap for the Romans. The Carthaginian infantry gave up the middle in order to attract the opponent, an opponent convinced of easy success.

Historian Polybius recounts us this battle: “Then, the Romans, pursuing them towards the middle, in the place where the enemies surrendered, they entered… so much that from both sides, armed Libyans were in their flanks. Those from the right side turned to the left and attacking from the right, they were threatening their enemies; and those on the left, turning right, were arranging on the left. Moreover, this also shows what arranging had to be made. According to Hannibal’s plan, the Romans occupying the middle were beleaguered by Libyans while they were pursuing the Celts. Turning toward those who were attacking them from the flanks, they no longer fought on manipulation, but man against man and all against all”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nzHDzUGhuTI

The worst Roman military defeat

Carthaginian victory was complete. The battle of Cannae was the worst Roman military defeat. Polybios informs us that 70,000 soldiers sacrificed themselves to save Rome (from 6000 horsemen, only 70 managed to escape, 300 allies took refuge in nearby cities, 10,000 pedestrians became prisoners).

L. Aemilius Paullus died like a hero in that fierce battle, and the reckless Varro “took the shameful path of escape and who did the magistracy useless for the country”. Livy gives us another statistic of military losses: 45,000 human losses, 3,000 pedestrians and 1,500 horsemen were taken prisoners and the Punic losses amounted to 8,000 deaths (Polybius records 5100 deaths).

But this victory was not harnessed. Hannibal’s indecisiveness heading to Rome (fully justified due to the exhaustion of the army) saved the Eternal City from being conquered, although the Roman confederarion was shaken under the blows of the Carthaginian.

Maharbal, Punic cavalry commander, told Hannibal some outstanding words: “Hannibal, you know how to win, but you don’t know taking advantage of victory!”. In 202 BC, at Zama (Africa), Carthaginian army, led by the experienced Hannibal, was defeated by the Roman legions under the command of Publius Cornelius Scipio (named “the African” after this victory), son of the man who was defeated at Ticiunus. Peace from 201 BC has ended the second Punic war (in harsh conditions for Carthage).

Hannibal’s military successes on Italian land were possible due to a fragmentation of Roman army leadership, due to his surprising maneuvers, forcing the enemies to accept confrontations in unfavorable situations, due to his ingenuity in maintaining a permanent tension among the opposing commanders and not least due to his military genius!